| PROLOGUE | |||

| 4. Backspin Classic |

I had started to raise pigeons again in the USA around 2007 when I was reintroduced to my revived hobby by local Florida pigeon breeders. Until that time, I had no idea what the Roller breed was since I only raised Turkish Tumblers in my native country, Turkey, while my older brother raised Adana Dewlap pigeons. The first time I saw Rollers fly, I saw a Roller rolled-down and hit her head on the concrete corner of a roof and killed herself right in front of me. I initially thought this breed was not for me since I was told incidents like these happen from time to time. “What do you mean they are unable to stop rolling?” I asked. “I think I’ll just stick with my Tumblers.” Then I fell in love with their rather unusual acrobatic ability to roll together and have been raising Rollers since 2007. I think having seen the colors I had never seen before, like Andalusian and reduced in this performing breed, played a big role for me to start breeding Rollers. Thankfully, most of local Florida flyers introduced Carolina bloodlines into their stock, so untraditional Roller colors are found in nearly all lofts in South East Florida. Not only Rollers came with variety of colors; the expected performance time was also much sooner than Turkish Tumblers, which made them more rewarding and desirable. In Turkish Tumblers, it takes a good year before you get good results, whereas in Rollers, you could get satisfying performance results as early as four months of age.

The first year I started to compete in the NBRC’s 11-Bird Competition was 2010 when Florida was added as the third state to join the Georgia-South Carolina region. This tri-state NBRC region for Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina became even more special for Florida fliers in 2011 because a few Roller breeders from the west coast of Florida came by to watch us compete in the southeast. This was good news for Florida because the flyers from the west coast were planning to compete with us the following year. When that happened, we were hoping to become our own region in 2012, separating from Georgia and South Carolina. We thought the state of Florida had enough flyers to support itself as a separate region. We also thought since all Florida flyers had never competed in a national competition before, it was not fair for us to compete against veteran flyers in Georgia and South Carolina. All I had to do was to step up and become the Regional Director of Florida if the new region was approved by the NBRC.

When the Georgia-South Carolina Regional Director, Ty Coleman, called us and asked us if we wanted to fly in the NBRC competition in 2010, Roller fliers in Florida were thrilled. We had some serious guys in Florida, and we knew we would be good competitors in the near future as we gained more experience flying in competitions. We were also told Florida used to have many good competitors when guys like Frank Surber, Richie Marengo, and Sam Gates flew Rollers. When these great fliers passed away, flying Rollers competitively in Florida slowly died. So, 2012 was a good chance to resurrect Florida in the NBRC competitions, and I was glad I was part of this movement. Ty Coleman, who was our Florida-Georgia-South Carolina regional director, and the judge, Cliff Ball, who was judging our region for the second year in a row, drove down to Florida together and we had two great days of flying Rollers. I remember getting very excited when Ty told us that he knew James Turner, and he visited James often since he lived only two and a half hours south of him.

I always felt lucky to see a variety of colors in Rollers that the Florida fliers had, and some of them were into pigeon genetics, so having and flying colored Rollers were no issue in Florida. Some of them even met Tony Roberts and James Turner in person before and acquired their bloodlines. Thus, I knew who James Turner was, and I had been a fan of his ever since I’ve seen the beautiful colors he had introduced into Rollers. When Ty told us how well he knew James, I asked Ty if I could get his phone number since Ty knew I was very much into pigeon genetics. I will never forget the first phone conversation I had with James Turner. I was literally speechless and didn’t have much to say, so I let him lead the conversation. He said he knew who I was through Ty and from my pigeon genetics website. He said he was happy that pigeon breeders like me were around to learn and study genetics. He was happy to know there were many other people all over the world who also appreciated the performance of Rollers as well as their colors. When I finally managed to speak, I told him how much I envied his accomplishments—putting color into spin. James was very happy to hear that I wasn’t one of those guys who are not fond of what he does in his backyard, breeding different colors to make dual purpose Rollers.

I have always appreciated what James Turner accomplished even before I met him and felt fortuitous that someone before me, who has a lot more experience in flying exceptional quality of Rollers, did what I had planned to do. My goal was also breeding and flying exceptional performing Rollers that also have exceptional colors. I never understood the problem some people had with that idea. If that does not promote the Roller hobby, I don’t know what could. James said, “Some people in the past called me a color breeder. But my birds can perform just as well as theirs, and mine look much better than theirs,” and I couldn’t agree with him more. When we were ending our first phone conversation, James told me that I could call him or visit him in South Carolina any time I wanted. That day, without a doubt, was one of the happiest days of my life. I had heard a lot about James Turner and his legacy, and I was proudly flying some of his family of birds. However, I didn’t own a single bird banded by him. Most Turner family of birds I had were mixed with Smith/Plona or other families by the local Florida fliers. I had a few more phone conversations with Mr. Turner, and I was very excited by the thought of visiting him in South Carolina one day.

After a long day of flying Rollers in southeast Florida, I dropped Cliff and Ty off at the hotel that I had arranged for them. Ty invited me into their room and showed me some of the videos that he recorded, interviewing James Turner. I must admit, I was very jealous of Ty, but I was also happy that Ty was recording “Mr. James” as Ty always called him. I thought it was very important for future generations to learn about James Turner and understand his methods to breed top quality Rollers with beautiful colors. This way, anyone criticizing James Turner without even watching his birds once, would understand how much time and effort it takes to perfect a newly introduced color to spin. I always knew acquiring knowledge of basic genetics is the simple part, but having the patience and ambition to complete a project is a completely different ball game.

2011 NBRC SC-GA-FL Region

Left Picture - 1st Row: Arif Mumtaz,

Ken Wood, Ty Coleman, Tom Lincoln, Cliff Ball,

Loui Bigay, Delroy McKoy. ~~ Front Row: Jeff Matt, Carlos Palamino

Right Picture -

Arif Mumtaz, Cliff Ball, Ty Coleman, Wendell Carter, Don Simpson

When the Florida portion of the fly was over, Ty invited me to visit them in Georgia and South Carolina to watch them fly and possibly stop by James Turner’s house on the way. This was an offer I couldn’t refuse. Not only did I have a chance to meet James Turner, I also wanted to see the nationally recognized competition flyers. So I decided to fly up there and finally meet James. I was told to show up at Don Simpson’s house in Anderson, South Carolina first. Cliff Ball drove down with another well-known Roller guy in the hobby, Wendell Carter, from North Carolina to meet us at Don Simpson’s house as Ty and his wife, Tiffany, drove up from Georgia. When I watched Don Simpson’s first eleven birds kit score 240 points and his second kit score 140 points, I knew right away that I didn’t know anything about flying and breeding Rollers. That was, to this date, the best performance of Rollers I have ever seen in an NBRC competition. His birds kept rolling, and rolling, and rolling even after their 20 minutes was over. As I was watching them and trying to write down the scores that Cliff Ball was calling out, I knew I had to improve a lot. Don Simpson was clearly way out of my league. He was retired, so he had the time, experience, and most importantly, the family of birds he was breeding and flying for years. It was a great eye-opener for me. I knew where I was compared to the top flyers in the nation, and I knew what I had to do to get to their level. Don Simpson won the NBRC’s National Championship Fly in 2010, and in this year’s regional, his birds had already scored much better than they did last year. I figured watching the most experienced competitors and seeing the quality of their birds would make me better prepared for future years if I was to win a competition. Visiting Don Simpson alone and watching his birds in a competition was definitely worth the trip.

After we left Simpson’s house, we drove down to meet James Turner. I was very eager to meet him finally, and I was thinking about some of the genetics questions I wanted to ask him. I was driving alone with my rental car, following Ty and his wife while Cliff Ball was driving down with Wendell Carter. When we got there, Danny Joe Humphrey from colorpigeons.com had just finished interviewing James Turner about genetics and performance. When I finally shook hands with James Turner and looked him in the eye, I knew right away he was a classic Southern gentleman. After welcoming us to his back yard and giving some birds that he had promised to Ty, James spent some time with me, showing me his setup. He seemed very down-to-earth, very welcoming, and very personable.

Summer of 2011 - Meeting James Turner for

the first time.

We started the tour in his kit boxes first and talked about his extreme dilute (lemon) birds. I have been reading debates between Ron Huntley and Paul Gibson about the genetic makeup and naming extreme dilutes in Yahoo’s Pigeon Genetics group. Some called it lemon; some called it ecru, and some called it extreme dilute, and I was quite familiar with the mutant although I have never seen one in person. When James asked me if I’d like to have a lemon Roller, I don’t think I’d finished saying the word “yes” before he went around me to take a bird from one of his kit boxes to hand it to me. He then asked me if I brought a carrying cage with me. Because I was speechless, all I could do was shake my head, so he found a used shipping box and brought it to me. Since I was holding that bird so tightly with both hands, while he went to get a box, I could not put my jaw back to where it belonged until my both of my hands were free. Let me explain why this was a big deal. This happened in 2011, and you could count the people in this planet who might have lemon Rollers with one hand. I finalized this chapter of the book on January 2018, and I bet you the number of people who might have lemon Rollers is still countable with fingers of one hand. Thus, when I was finally able to speak, I first thanked him for giving me the bird and then asked him if he had any idea how rare this color was. His response was prompt and to the point: “Yep!”

When we got down to the last kit box, where he kept his top performers among many other non-traditional colored Rollers, I noticed one bird almost immediately. It was a beautiful reduced white bar bald head. It was the most beautiful reduced bar I had ever seen. I think there was an additional gene in this bird, which made the wing shields darker than normal to show that perfect white bars in them. James said that those last two kit boxes at the end contained his best performers. All his kit boxes were categorized by their age and performance level, regardless of their colors. He said these birds, indicating the last two boxes containing older birds, would fly in anyone’s competition kit, and he was so confident saying it. I suppose James wanted me to know that his main goal has always been to breed for best performance regardless of colors. He wanted me to know there was a reason why all these nontraditional colored birds were located in his top kit boxes—they were there based on their quality of performance.

James and Vickie live in a very nice house with a big back yard on a one-and-a-half-acre property—a perfect place to breed and fly birds. He has four different sections for his birds. The first section is designed for his flyers and has about 12 different kit boxes, six on each side. This kit box building is 16 feet long and 11 feet wide with a four foot walk-through in the middle. Each kit box is 42 inches deep and 32 inches wide with 24 box perches in each kit box. The second section has individual breeding cages and two big sections in the back, where breeders are kept but separated based on their gender. These are all of his proven birds based on their aerial performance. If I had to guess, I would say about 70 percent of them were nontraditional colors and some of the best colors and types I have ever seen. I could spend days just admiring the looks of these breeders. If it were me, I would call that area the “mission accomplished section,” where the most attractive birds with top performing quality were located. The third section was even more interesting to me. Mr. Turner called it “the gene pool,” where he kept his project or work-in-progress birds. At that time, he was working on putting ice color into Rollers but he also had a ton of other project birds there, including amazing chimeras, ribbon-tails, pencils, reduced rosy necks, toy stencils, and frill stencils.

James Turner's kit box setup - six kit boxes on each side. Names of his dogs hanging on each side.

After James gave me the tour of his backyard, he and I started to talk about genetics in front of Ty, his wife Tiffany, Cliff Ball, and Wendell Carter. This was about the time I had just learned about the subject of crossover of genes from Dr. Richard Cryberg, and I knew many people in the hobby did not truly understand the concept of crossover of genes even though it is a fairly simple mechanism. For whatever reason, I decided to impress James with my genetic knowledge, so all of a sudden, our little discussion sounded like we were arguing about crossover of genes. We were talking about the distribution percentages of chromosomes and genes in F1, F2, F3, if we cross a Roller with a Homer, etcetera. So an F1 offspring would be 50 percent Roller and 50 percent Homer. Then, if we take the F1 and cross it with another Roller, then the F2, in theory, would be 75 percent Roller . . . unless, I said, we leave the crossover mechanism out of the equation. Otherwise, the percentage in F2 should be 75 percent. It was one of those awkward moments when instead of keeping my mouth shut and listening, I mumbled a response in front of a person that I have so much respect for. To make matters worse, instead of ending this nonsense, I decided to argue further with him to prove my point, as though I had to win the argument. I have no idea how we got there, but I guess I felt the need to prove to James that I wasn’t an average roller guy—I knew my genetics. So I decided to get two same-length flight feathers I found on the ground, lined them up side-by-side, and attempted to show off my knowledge of crossover of genes. I got on my knees, pointing at the feathers lying on the ground as though they were a pair of chromosomes and explained how genes on the pair of a chromosome can be exchanged during crossover. James finally decided to end this nonsense and said “Okay!” and just walked away politely. Ty, Tiffany, Cliff, and Wendell were smart enough to stay out of this conversation as they were watching us with awe.

Boy, did I feel stupid and embarrassed when James walked away. What was I thinking, arguing about genetics with the person who has much more expertise and knowledge than I? Thankfully, later on James and I concluded that we were basically saying the same thing, but we were using different words to describe it. I was so happy to know he finally understood what I was trying to say, but I am afraid I was not home free yet. That incident left me with Ty giving me a nickname: “Feather Boy.” Ever since that day, every time I meet Ty and Tiffany, they make sure to make fun of me about that incident, and I really don’t have any comeback for them. They wouldn’t even say a word, other than handing me a feather or two, or simply asking somebody else to hand me some feathers, and then chuckle. This happens in every gathering we attend together, in front of everybody, and thankfully, nobody else in the crowd knows why Ty or Tiffany is handing me feathers, followed by big laughter. Yup, that’s what I got for not shutting my mouth when I should have been listening.

Left

Picture - One of James's top performing kits with unbelievable

colors.

Right Picture -

Tiffany Coleman found my name tag on the ground, in one of the events took

place at James’s house. She put the initials of Feather Boy next

to my name and stuck it on one of James's breeding boxes. The tag

still remains there today,

and I hope nobody is asking James what FB stands for...

We spent a little over two hours at James’s house, flying birds and talking about them. When James was speaking, we were all listening with both ears. Although James never received formal training as an instructor, I could tell he had a unique way of teaching things. One of the things I noticed immediately was he made learning fun and interesting. One of the kit boxes contained all the birds James culled. These birds were either roll-downs, did not keep up with the kit, were mediocre performers, or for whatever reason, did not meet the standard James was looking for. This box is called the “take me if you want me” box. But if you get a bird from that box, it was clearly explained to you why that bird was a cull, so you knew what to expect if you took it home and bred from it. So, James took a bird from that box and said to us: “This bird is a roll-down. Hold this bird in your hand, and tell me how you could tell it is roll-down.” I became very excited, thinking James would tell us how we can tell if a bird is a roll-down just by holding it in our hands. Some people in the past claimed they can tell a roll-down just by holding them, but they never gave any explanation how they did it. “If I toss this bird up, it will come right down and crash. Do you know how I know that?” asked James. Although I, too, handled the bird like the others did, and looked for any physical characteristics of the bird to get a clue, I decided to stay out of this game. “Nope! I am not going to make another comment about feathers or feathered animals today. I am just going to listen,” I said to myself. After Ty, Wendell, and Cliff guessed their answers, James took the bird back and said: I know it is a roll down because she rolled down on me last week!” We all had a good laugh about it, realizing the only way to tell a roll-down is by flying it.

The second quiz question was just as interesting, as James was challenging us to think while he was educating us. He picked two random birds from his kit boxes, and he let us handle them both, one at a time. But he didn’t let us handle each one for more than 2 or 3 seconds. Then he asked us to tell him the differences we noticed between these two birds. They all went for the obvious and told him about the body size and shape of the bird, keel size, feather quality, etc. While we are expecting James to say, “One of them is a champion because I see it perform every time I fly it,” instead he told us that we made a common mistake and did not notice the strength of the birds. He said when he handles a bird, first thing he checks is the chest muscle and how strong the bird feels in his hands. According to James, that tells a lot about the performing ability of the bird. He handles his birds regularly before and after each fly. “There are some people out there thinking the birds should feel like an empty shell in your hands—very light and no strength at all. Now these birds can spin, but these kinds of birds normally don’t have any quality in them. In my opinion, the key to flying good Rollers is that you gotta have them in the right condition, like the way you train athletes. If they are too strong, they won’t roll as much, and they’ll fly too high; if they are too light, they will roll frequently but lose quality and depth. So as a breeder, it is your responsibility to feel your birds and notice the difference in their strength, and compare their performance in the air. This is also the reason why I strongly believe in having one family of birds. It is important because if you are flying multiple families of birds, it will be very hard to feel their strength and compare them with one another. If you stick with one family, you start learning about them a lot faster. If you are a serious flyer, you develop these things and start noticing everything and paying attention to every detail. The type is also important, but not all birds need to be exactly the same type; this is why everything I do is based on performance in the air. If a bird can really spin with high velocity and quality, it has the right type, in my book. We all like these apple-like upper body, short keeled, and cubby birds, but type by itself don’t mean much if the bird can’t spin in the air. I really like half-brother half-sister mating. When you see your birds perform in the air, you also need to know which parents these birds came from, their body type, history of how they’ve developed etcetera, and in time you start learning from your experience which type of birds needs to be mating in order to get maximum performance out of their babies. So, I don’t follow absolute pretzel breeding pattern without any exceptions. In my family, I also have sub-families like Rambo and 007. So I also keep that in mind when I choose the mates. But how they performed and how they developed in the air are the main factors in choosing them as breeders,” said James.

When Ty said it was time to leave for the next flyer’s house, I really didn’t want to leave James’ house. I felt like a child in a candy store, and I was really enjoying the way James was sharing his extensive experience and knowledge. I asked James if I could stay and spend the afternoon with him. He didn’t have any problems with that idea; he knew meeting him in person was the main reason I flew up to South Carolina. I told Ty I would see him the next morning at his house in Georgia to watch his birds fly before driving down to Fort Lauderdale. “No problem, feather boy! I’ll see you tomorrow,” said Ty. He knew meeting James Turner and spending some private time with him was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. I had a lot of things I wanted to talk to James about: genetics in general and Rollers.

Left

Picture - June, 2013 at James Turner's backyard. Ty Coleman

gave me a pair of feathers, yet again!

Right Picture - June, 2016 at James

Turner's backyard. Tiffany and Ty sent their youngest daughter

Kristin to hand me a feather. Bless her little heart.

When I was alone with James, I told him that I was relatively new to genetics and in flying Rollers. “I am afraid I will be a beginner for a long, long time since there is simply so much to learn in both fields,” I reflected. Genetics became another interest of mine ever since I learned the basic Mendelian genetics in high school, but there is simply so much to learn in genetics to become an expert. Pigeons give us lots of mysteries and genetic material to work with. From the time I owned a Turner bird and saw the quality of spin and the colors he put into them, I became hooked on doing the same thing. Ever since I read the article “Man Who Put Color into Spin,” written by Cliff Ball, I wanted to meet James Turner. I do not know if Cliff Ball realizes how many Roller breeders around the country would read that article and be influenced to meet or buy birds from James Turner. But they would also be surprised when they found out that James Turner doesn’t sell birds, and spends hours talking to pigeon fanciers on the phone every day. Seeing that he still promotes the hobby by producing the most attractive performers with same delicacy and hard work year after year made me envy him even more. When I met him and saw what he had been working on, I said to myself if I ever become half the man he is, I would call that a great accomplishment. If I could get a unique color on a champion Roller the way he did, I would be very happy. However, thanks to his generosity, my main goal in producing colored birds changed when I met him. My new goal became to take what he did with Rollers so far and bring them into the next level. To be honest, I still don’t have a clue what that next level is since there is not much room left to improve the quality of his birds’ performance. But I knew if I could somehow continue to breed quality spinners with attractive colors, his legacy would move forward and not be forgotten.

We live in a time that if you do not keep up with changes in genetics, what you know will quickly be outmoded by new learning much of the time. The fact is, genetic science is very challenging and takes a lot of time and requires patience to study, and we can say the same thing about flying and breeding a winning kit of Birmingham Rollers. Evidently, if you are not patient and don’t like to challenge yourself, you won’t be good in either field. Knowing and understanding genetic science and looking at the birds produced by James Turner over the years says a lot about the man. It says that he is a hard worker, he has a tremendous amount of patience, and he must be a brilliant pigeon breeder to get these kinds of results and respect from many breeders all over the nation. Although no one truly understands what causes Rollers to roll yet, we are assuming at least three or four genes are responsible, and they seem to be very complex genes. James and I both agreed that the rolling ability cannot be a single recessive gene as some people firmly believe. There must be other factors involved in rolling. If it was that simple, we could make Homers roll 30 feet in the second generation. The fact is, we don’t fully understand what causes pigeons to roll or tumble yet. I think the key is to find the median of all the genes required for a champion Roller, but it is a very hard task to even produce a true champion Roller to begin with, especially when we include epigenetics into the equation.

While we are talking and looking at his birds, he picked out two beautiful, young qualmond birds from his training kit boxes. These birds were just a few months old, in training to master their spins. He knew I might have an interest in a qualmond gene because I asked about them earlier. He asked me if I had to pick one of these two birds, which one would I pick. So I held them in my hands, one at a time, and noticed the bald-head hen felt better in size and stronger in my hand than her brother. I was pretty sure I passed the test this time and told him I would pick the hen. To my surprise, he told me to put that hen in my box and take her home with me. I was very happy, but I couldn’t resist asking him which bird he would have chosen. I became happier when he said he, too, would have chosen the hen.

James Turner's breeding coops - walk through individual breeding cages and holding boxes in the back, where breeders are separated by their gender.

I realized James liked playing games, so I decided to play one with him. I gave him a scenario and said there was a fire in his loft and he had only enough time to save one pair of birds. “Which pair would you choose?” I was rushing him to make a decision. He hated to even think about the question. “Fire? Well, that’s horrible,” he said as he reluctantly started to walk to his breeding section. I said, “It’s only a game; just pick a pair.” He hated being rushed and said he had to think about it as he walked to where he kept his breeders. He showed me two cock birds right away. One was a blue bar badge and the other was a black-self with white flights. He said, “I would choose one of these two cock birds.” I insisted again and asked him to choose one—quick. So he picked the blue bar badge. Then he walked back to where he kept his hens, and without any hesitation, he picked up a black bald head hen. I was very surprised that he went for traditional colors, but I had a feeling he hadn’t picked them based on their colors. When I mentioned that to him, he said, “Okay, let’s talk about my choices. I care about the performance more than anything else. Color always comes second, but you didn’t give me a whole lot of time either. I don’t know what I would have picked if I had more time. Some projects take years to complete, but these two birds happened to be the best producers at this time, so I picked them.” I was very surprised with his first instincts to choose those birds based on their performance.

Later on, when we were discussing color and performance, James brought up this conversation when we were talking about his reputation of being a color breeder, and he said, “Remember you asked me to pick two birds, and neither one of them were colored Rollers?” When I said, “Yeah,” he continued. “Incidentally, that qualmond I gave you was the daughter of that black bald head hen.” I felt really lucky when I heard him say that, and I knew right away that I was going home with one of the good prospects. One thing seemed obvious to me: people calling James a color breeder bothered him. Even he tries to ignore them. But I couldn’t have picked a better scenario to prove it otherwise. Yes, James Turner breeds colored birds, and he does a wonderful job putting different colors into Rollers. But what some people choose not to see is that without the top quality performance, colored birds are absolutely worthless to James. “I breed for spin just as hard as other people do,” he later volunteered. “If you had asked me to pick a pair during the time when I had Rambo or 007, the color choices would have been different,” James reminded me. “But again, what good is color if it can’t spin?”

James Turner's Pencil and Reduced Rollers

When I asked James about how he dealt with the pressure and the trash talk he received from the others about the unusual plumage color of his Rollers, James responded: “They started to call me or anyone who had these, quote-unquote, ‘dual purpose rollers’ a color breeder. To me, a color breeder is a person who breeds only for color. This kind of ignorance about the performance of my birds still exist in the minds of some people today. What is unfortunate about these people is that they think I don’t care about my bird’s performance. They have no idea that my first and foremost priority is performance. Then again, how would they know that if they never bothered to ask me? You see, over the years I have discovered that if I talk to anyone long enough and listen to them, there is always something valuable I could learn from them, regardless of their background. I was raised to be open-minded and respect other people’s opinion and I’ve always liked talking to people. One of the things that really irritates me about some people in the hobby is when they refuse to listen and refuse to be open-minded. It surprises me how these fellas, without even meeting me in person or watching my birds fly once, can judge and criticize their performance based on their plumage color. So, after a while I have learned not to waste my time trying to convince them anymore, because even if they saw the performance of my birds with their own eyes, when they left my backyard, they still couldn’t see past my bird’s plumage color. Once my birds had landed and exposed their unusual colors, these guys conveniently forgot how well they had done in the air. They just could not handle the fact that these birds also looked pretty. Maybe these guys are simply color blind, I don’t know - it’s a genetic disease, you know...” chuckled James. “Randy Gibson once told me that some of these so-called legends in CA would come and see Randy’s birds fly. ‘That black self-bird is spinning good Randy, what is it out of?’ they would ask him when these birds appeared to be black selves in air. Randy would say, ‘I have to look up the pedigree when it lands, but if you really like it, you can have that bird when it traps in.’ Thinking they are getting a good performing bird, they would patiently wait for Randy’s kit to land. Once the bird landed they would notice it was actually Andalusian, not black. They then would come up with an excuse not to take the Andalusian even after they admired its performance in air. So my advice to you, Arif, is not to get down to their level and do the same thing that they are trying to do to you. Don’t go down to swamp with them. My father once told me never to argue with a stupid person, because if a stranger comes down the road and sees both of you arguing, he can’t tell which one of you is stupid. Having a discussion is one thing but disrespecting somebody is another thing and this attitude, along with peer pressure, really hurts the hobby, in my opinion. Back in the day, when my friends and I flew Rollers in our local clubs, we did nothing but talk about birds and we had great times. We never tried to tear each other down. If one of my birds rolled stiff, and if one of my friends told me that bird needed some work, I didn’t get offended by it. I knew he wasn’t trying to put me down, he was just letting me know of his true opinion. Arif, I really like people; I am a people person and I like to talk to them, but I have no time or patience for ignorant people. What these fellas need to do before they criticize my birds is get under a kit of my birds and then just look up,” said James with some frustration in his voice. “I try to treat people the way I’d like to be treated. I try to respect everybody and I expect them to respect me. It is that simple, and believe me, I am a very simple person,” James said.

We also talked about the importance of starting with a known family of birds. I told him how unhappy I was with my birds’ competition scores and why I desperately needed to improve the quality of my birds. Right off the bat, he advised me not to start with his family because he simply didn’t want to influence my decision. “Some people might give you a hard time if you flew my family,” he said, giving me a fair warning about some people in the hobby. He advised me to pick any family that I think would work for me and told me that sticking with one family would make my life a lot easier. I protested and said, “Well, if I start with a known family and just fly them and breed them successfully, where is the accomplishment in that?” He both agreed and disagreed with the way I was thinking. He said, “Creating a family takes a lot of time and expertise, but not everyone has to go through this. Even if you pick a proven family, there are many challenges to learn about that family and there will always be room for improvement. There will always be something that can be improved about their performance. I have never seen a perfect Roller. 007 and one of his daughters were as close to perfect Rollers as I can imagine. The only reason his daughter was not perfect was because she didn’t make Rollers just like her. If you are ever satisfied with your birds, then you will lose interest. There must always be a challenge, something you could do to improve your birds. If you are starting with good stock, you will produce some good quality Rollers, but maintaining that quality is the hardest part. Raising good Rollers with color in them is very, very difficult. My advice to you is to challenge everything you have been told. When that egg cracks, I look at the color of the beak. I start looking at the length of the down. I start looking at anything and everything. Don’t reinvent the wheel, but just take the wheel and make it roll smoother.” Then I said, “Perhaps I will start with your family and try to take them to the next level.” He liked the idea right away and said, “Now, remember it was your decision to choose my family,” then he paused. “But I hope somebody who has a genetic knowledge in pigeons continues to do this with my birds,” James said with ambition in his voice. But one thing was sure. He was being very careful not to influence my decision about choosing his family of birds out of other well-known families. That afternoon, I realized James and I became lifelong friends.

Left

Picture - March, 2015 at James Turner's backyard. James

is teaching me how to use his Z Turn Lawn Mover.

Right Picture - March 2015, James

and I visited Jimmy Waters (far left) as we generally do, whenever

I go up to South Carolina. Greg Truesdale (far right) came to see

Jimmy from North Carolina.

Another subject James and I discussed that day was the personality factor of the birds, which involves epigenetics of the rolling behavior. Are some of them too scared to roll, or are some of them simply daredevils? Are they smart and “in control” of their rolling ability and rolling impulse? Just this trait (personality) could make a difference between a great Roller and a mediocre Roller, regardless of its genetic makeup. This is why after many years of inbreeding a family of birds, it does not give any guarantees that every single offspring will be a champion Roller. The fact is that the rolling trait is very, very hard to maintain in the gene pool, and therefore selective breeding is extremely important and requires expertise. When you add complex color mutations and try to maintain both the color and the performance in an individual bird, it makes things even harder to achieve.

Toy Stencil is probably a good example of how hard it is to bring color into spin. We currently believe there are three or four genes responsible for a TS phenotype. Now, think about how James has to maintain three to four genes of rolling trait and all the genes for TS in a single bird. Those who do not understand the time and effort it takes to produce such a bird will never appreciate a champion Toy Stencil Roller. Over the years, on some Internet forums, I have seen people say that if Turner spent that time and effort in performance only, he could have been contributing more to the hobby. However, what these people do not understand is that James had already produced the top quality performing Rollers and dominated most of the competitions he was in. I assume at some point, winning must have become boring to him, and he must have decided to take the Rollers to the next level by making them not only champions of the air but also champions to admire in cages. He and his friend Tony Roberts took on probably the hardest task in Roller breeding. While many people are still struggling to produce good spinners, over the years James and Tony produced birds that can spin and look very attractive to any pigeon fancier. I think James’ competitive personality also had a lot to do with this. He was told it can’t be done; you can’t have dual purpose Rollers. Boy, did he prove them wrong!

James Turner’s loft is named “Rolling Rainbow Lofts,” which is nationally acclaimed for “Turner hot” Rollers, featuring nontraditional color birds that could spin. James breeds high velocity birds in beautiful colors of the rainbow. He also has a sign on his loft, although the words are now barely legible as they have faded over time. It says: Velocity, Control, Frequency, and Depth. According to James, he wrote them to remind himself daily of the primary goals that he was striving to accomplish. As time passed and he became an expert on breeding Rollers, he came to the conclusion that the word “control” was the key to success to breeding champion Rollers and that control was more important and harder to accomplish than velocity, frequency and depth. James admits that it was tempting at times to lose that focus in the face of a beautifully feathered Roller that had to be culled because its performance did not meet his standards. He was never impressed with mediocrity, regardless of pedigree or color. When he says he has never seen a perfect Roller, I think he feels he has created near-perfect Rollers with the majority of the projects he has started. But the reason he thinks none of them were perfect is because although he has the top-notch Rollers, he still feels we must never stop improving the quality of performance.

One thing I have noticed with his birds is how tame they are. For pigeons to be so tame, they must be bred from selected tame parents, and you should also handle your birds often, especially when they are young. I am sure that James’ getting up every morning to handle and study his birds had a lot to do with them being so tame. He breeds for that trait and avoids breeding from fierce birds. He believes there is a correlation with intelligence and their tameness, which makes a lot of sense if you think about it. For a pigeon to trust its owner as a pet would, and not be afraid is a big part of performance and responding to training.

After spending many hours with his birds, I was invited into the house to continue our conversation. When we sat down in his study, which was loaded with trophies, books, and a couple of computers, James started the conversation by admitting that he did not invent the spin in Rollers. He doesn’t understand everything there is to know about genetics of rollers either, but he figured out how to put color into spin. “I know how to get where I want to go when I do a project,” says James. He no longer calls his birds Birmingham Rollers; he calls them South Carolina Flying Rollers. According to James, Birmingham is a place and Roller is a performing breed, and he chooses to concentrate on performance, not a place. He breeds them in individual breeding pens and keeps excellent records of his birds on his computer, but he also has hard copies of his pedigrees as a backup. He doesn’t sell birds but give them away to anyone who wants them, if he has any to share. When he does, he always gives his best performing birds to people. He believes if he himself is not hurt giving his good birds away, he is not really helping that person. Unlike some people, he believes new guys should start with best quality birds so they can stay in the hobby.

One thing very noticeable about James is that he tries so hard to never misrepresent his birds and doesn't give pedigrees when he gives his birds away. He simply doesn’t believe that every bird from his family will be a champion, and no one on this planet can claim that about any other families either. James believes people should air test them before they could breed them, instead of breeding them based on their parents’ band numbers. James strongly believes breeding by pedigree or by known family is the wrong way to breed pigeons. He believes pedigrees are only good for keeping good information, not to be used as an advertisement.

I asked James what he would advise for guys like me who want to continue James’ legacy by trying to improve the quality of spin and add additional colors into Rollers. He said, “Whatever you do, do not abandon the project in the middle. That’s the reason we got a bad reputation—when people never finish projects they have started. Because some projects are never finished completely, people think color birds can’t spin. Just don’t put junk out there and claim they are Rollers. Don’t give people any reason to believe color birds can’t spin. Our job is harder than most people’s. To prove our point, we have to go above and beyond producing a good Roller. That means our Rollers must spin just as good as theirs or better. Be serious and be patient with your breeding program, and never put a bird out there until you feel that bird deserves to fly in a competition kit.”

This answer was surely an eye-opener for me. I suppose these challenges that James faced early on made him work a lot harder to produce better quality Rollers. Could he be as good a Roller breeder and flier if he didn’t do color projects? There is no doubt in my mind that he would be. But I also believe that trying to prove to the rest of the world that his Rollers, regardless of their colors, can spin just as well as others, if not better, made him more eager and helped him produce a much better quality of Rollers.

I asked James how he would want to be remembered in the hobby. His response made me a completely different man today. I could never forget the sincerity and emotion in his eyes when he answered this question. “I would like to be remembered as a man of integrity because if you don’t have integrity, you have nothing! If they say I flew some good Rollers, too, that would be fine,” he said. This was the first of many times I heard him use this powerful word – INTEGRITY. However, it took me awhile to understand what this word really meant to him. The people who have high integrity are the people who always do the highest quality of work in everything they do. They are the people who are always honest with themselves, and they strive to do excellent work on every occasion because to them, everything they do is a statement about who they are as a person. For James, integrity is the foundation of his unblemished character, the core quality of a successful and happy life. The more I spoke to James, the more I learned the essential value of being honest. As a result, I will always remember James as a man of integrity, and that’s the reason why I chose that phrase for the title of this book.

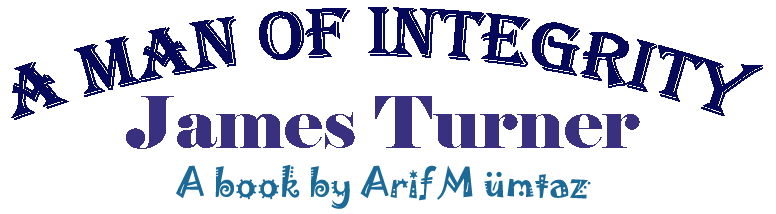

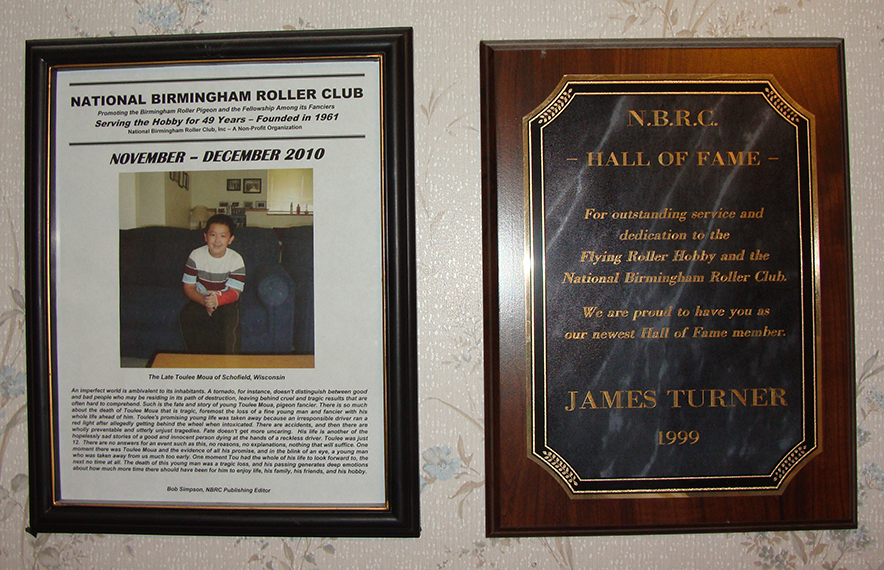

The last distinctive moment I remember about that extraordinary day was the picture of a 12-year-old Laotian-American boy named Toulee Yang, printed on the front page of an NBRC bulletin, hanging on the wall of James’s study, along with trophies, plaques, and hand-painted pigeon pictures. When I read the article, “Drop a Pebble in the Water” by Cliff Ball, I remember being jealous of the young man in the story because he was in communication with James Turner. I thought to myself how lucky this young man was. He was so smart, well-read, and so eager to get in touch with his hero, James Turner. After pleading with his parents for couple of years, Toulee convinced his father and uncle to build him a small kit box, help him buy a pair of birds, and finally…finally, allow him to contact James. I could only imagine the happiness this young man felt when he was finally allowed talk to James on the phone. I think he was thrilled when they arranged for Toulee to go visit James and meet him in person. When I first read this article, I remember having blurred vision towards the end as my eyes became watery. I was so heartbroken and upset. Toulee passed away in a tragic accident, never having a chance to meet James in person.

Toulee's NBRC Bulletin picture hanging next to James's Hall of Fame Plaque

While sitting in James’s study that day, and having one of the best afternoons of my life, I asked James about Toulee. It was obvious that James was truly impacted by this young man who came into his life and left suddenly and tragically. James regrets not shipping him any birds before meeting Toulee in person. “I wanted to meet him in person, and I wanted him to pick the birds he liked,” James admitted as he became emotional talking about him. Then James shared something incredible with me, and I believe to this day, I am one of the few people he shared this information with. Toulee spent $30 and bought some birds that were supposed to be Rollers. He had never given up on these birds and did everything he could to watch them roll once, but they never did. That bothered the heck out James, why people would sell to a young boy birds that didn’t even roll. So in Toulee’s honor, every time James has a pigeon-gathering at his house, he picks out the two best performers, ideally the ones that also have good color markings on them, and puts a snap-on band on their legs with Toulee’s name written on it. Ever since Toulee passed away, James has been flying birds in his honor. “I flew two for Tou at every gathering, in honor of him, and I will continue to do this as long as I fly birds,” said James. “Two for Tou,” he said as he looked away, trying very hard not to break down.

I wish I could have spent days with James, but I had to leave late that afternoon. James sent me home with excellent birds that day, and I couldn’t be happier and more grateful to James. On my way down to Florida, my last stop was Ty Coleman’s house in Georgia to see him compete the following morning. Ty and his wife Tiffany keep their Turner bloodlines pure. Although Ty had a bad fly day, I could tell he had exceptional spinners. What I remember most about that day is the Colemans’ generosity in sharing their birds as well as their hospitality to their guests. Evidently, James’s unprecedented benevolence had an impact on Ty and Tiffany. They sent me home with at least ten birds that day and quite a few of them came directly from Ty’s first competition kit. These were all first generation Turner Rollers whose parents were banded by James. I have been friends with Ty and Tiffany ever since, and I feel privileged to know them and call them friends, no matter how many times they would hand me a feather or two every time I see them. Ty and Tiffany are two of the true ambassadors of the Roller hobby. As James says, “I wish there were more people like Ty and Tiffany around everyone. You can always depend on them to promote the hobby by sharing their best birds with anyone and providing any help a beginner would need to start and stay in the hobby.”

On the way home to Florida, I called James and told him how happy I was to finally meet him in person, how much fun I had talking to him, and how much I appreciated the birds he gave me. I said, “Well, now where do I go with these birds? You and Ty gave me top performers, and they have exceptional colors. You haven’t left any room for improvements . . .” James didn’t hesitate to finish my argument and said, “Arif, there is always room for improvement! In fact, you now have the challenge of not only maintaining their dual-purpose qualities but also improving them. I think you just signed yourself up for the hardest job in the hobby!”

James

is without

a doubt

one of

the most

influential people

I have

ever met

in my

life. I

was never

the same

person after

I met

him. Not

only had

my whole

perspective of

breeding pigeons

changed after

meeting him

that day

but my

personality has

also changed

for the

better. Above

all, I

had to

redefine my

definition of

generosity, as

I have

never seen

it practiced

like that

anywhere else.

He built

trust with

his integrity,

charisma, ambition,

confidence, energy,

open-mindedness, and

his authenticity

by being

himself. He

had a

profound impact

on me.

While what

people are

influenced by

generally changes

with the

season, the

unique habits

of influential

people like

James remain

constant. He

is that

unique person

who is

never satisfied

with the

status quo

as he

constantly asks “What

if?” and “Why not?” He is never afraid to challenge

conventional wisdom, not for the sake of ruffling feathers but to make

things better. I wish everyone could see the labor of love James pursues

behind the scenes every single day. Only then would the Roller hobby

become the hobby every hobbyist would want to join in order to share

his or her passion with others, unselfishly and with pride.

All rights reserved (c) January, 2018 by Arif Mümtaz.